David Howell of the UK Christian Youth Work Consortium takes us through the challenges facing the UK church in its support for children and young people

If only….

If only we had more children and young people in church.

If only we had more volunteers for our current work with children and young people.

If only we knew how to make the building more effective for youth work.

If only we knew how to make worship more effective for young people.

If only we could get into the local schools.

If only we had someone who could do something with the young people who hang around outside.

If only we had someone who could communicate Jesus to the young people.

Then the rich man said, “No, that’s not enough! If only someone from the dead would go to them, they would listen and turn to God.” (Luke 16:30)

We are not specifically looking for the resurrected and risen Christ to turn up at our church and transform everything – although that would be brilliant. But we do need answers to these questions. For many churches and Christian agencies in the last few decades, the answer had been found in employing trained youth and children’s workers!

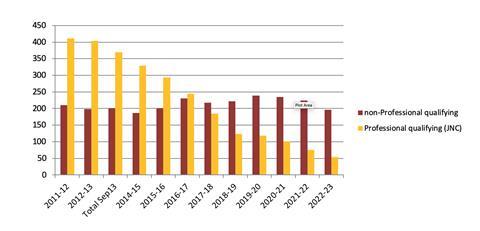

It was back in the early 1990s that research was published indicating that between 1979 and 1989 it [the church] lost 155,000 teenagers, the equivalent of 300 a week[1]. As a result many churches and Christian agencies took hold of the issue and started investing in training for Christian youth work, youth ministry, children’s work and children’s ministry. Theological Colleges and Christian training agencies created courses and by the early 2000s the numbers in training, preparing to serve the Kingdom through work with young people were increasing almost exponentially. Moorlands College, Oasis College, Nazarene College and the Centre for Youth Ministry (CYM) were creating programmes to train a huge tranche of people who would have the competence and skill to work with children and/or young people. At one time CYM was recruiting 60+ students a year to train at its five regional centres around the UK.

And then, in 2008 the financial markets crashed and sent a seismic tidal wave of recession around the world!

The downturn hit youth work in England, with austerity measures seriously impacting government spending and reducing the funds available to local authorities. As a result, over ten years the spending by those local authorities on youth services collapsed by 70%. Churches and Christian agencies felt the pinch and the numbers of employed workers declined as employers struggled to reduce costs and make ends meet! Added to which the reduction in the commitment of the government to youth work soon became an example which other institutions followed, and the commitment to effective work with young people declined nationally. And as it declined, both in society generally and in churches in particular, so there were less role models for young people to look up to and follow into a future career!

From the early years of the austerity measures, and the impact on churches and Christian agencies, we have seen a drop of 60% in the number of students in training to serve the church in youth work, youth ministry, children’s work and children’s ministry.[2]

And Covid has not helped! Just as we were beginning to think that maybe we were climbing out of the decade of austerity, and political parties were beginning to talk about investing in work with children and young people, so Covid-19 hit. As a result we have seen a further decline in numbers in the church, together with the emotional hit which children and young people especially felt. Sarah Holmes and a group of international researchers noted that

There are indications that for the majority of children, the pandemic adversely affected their faith formation. Hence, there is an urgent need for church leaders and para-church organisations to lay out clear and effective strategies for the seasons ahead[3] (Holmes et al 2021)

And then just as we were coming out of Covid, Russia invades Ukraine and generates a world-wide rise in the cost of living.

Some of the original training providers are still delivering higher education programmes, others have had to close. During the academic year 2022-23 there have been 13 colleges/training agencies offering 29 Christian youth/children’s work/ministry programmes. Since the programmes began, many of them during the 1990s, most programmes have adapted to the steady decline in numbers by delivering more creatively (online and placement-based) or broadening the scope of the qualification (including children’s work, schools work and/or family work).

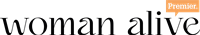

In 2011-12 there were 621 FTE (full-time equivalent) students on higher education programmes across the UK, specifically training in both youth work and theology, to be equipped to be people of faith to this emerging generation. But this year there have been just the equivalent of 250.5.

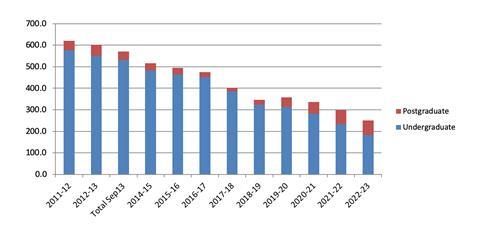

Back in 2011-12, for every one student undertaking a qualification in youth ministry, or working with young people, there were two students on programmes which also enabled them to gain the professional youth worker qualification (often referred to as the ‘JNC’). Today for every 1 student on a professional qualifying course, there are 4 students on general, non-professional, programmes. Whilst undergraduate numbers have dropped across the twelve years, from 575 in 2011-12 to 182 this year, post-graduate numbers have seen a 50% increase from 46.0 to 68.5, with many mature students returning to study, or using the part-time options available.

But it is not the fault of young adults failing to apply, there are a more complex collection of causes for the reduced numbers training to serve the church in the fields of youth and children’s work.

Under-valued

Many churches echo the “If only…” statements above, but then under-value the training. Research carried out last year by South West Youth Ministries found that over 90% of churches were indifferent to the value of qualifications for the Christian youth/children’s workforce.[4]

Research by Ali Campbell for the Bishop of Leicester a few years back: “Terms and Conditions of Salaried Workers” surveyed 637 salaried children’s, youth and families workers from across the UK and across denominations. 63 had a youth ministry degree or equivalent and 81 had the JNC qualification = 22.6% of the total workforce surveyed.[5]

That same research showed that, given the decline of student numbers across the last ten years, when looking at those who have been in Christian youth work/ministry for ten years or more (89) 81 had an appropriate qualification. 91.0% of those who have served longer than ten years have such a qualification, which suggests that the value to the individual, and to the enabling of long term work is very significant.

A recently published paper indicates that there is a quantifiable increase in attendance of children and young people in Anglican Churches in England who employ a Children, Families and/or Youth Worker It used original data collected by Youthscape and UK Christian Youth Work Consortium in 2015-16 to show that there is an average increase of 7 children/young people in a church, over against churches who do not employ such workers.[6]

Under paid

For many years there has been an un-written but widely accepted view that you move into youth ministry after which, as you mature, so you move into a ‘proper’ job, that of the ordained ministry! Whilst it is true that the skills learned in youth and children’s work can be transferred to the wider generational reach of most churches, it is also true that salaries for youth workers have not matched those for the pastoral/preaching ministry and thus as youth workers have grown older and wished to support families and homes, they have looked for more financial returns and greater security.[7]

Sam Donoghue, the Head of Children’s and Youth Ministry for the Diocese of London, suggested in Premier Youth & Children’s Work (March 2021 Vol 1) that the decline in numbers…

‘…seems to tell the story of how the role of the youth and children’s worker in churches has become more precarious and less valued. That has in turn led to less people being willing to invest in training in it in a way that commits them to staying in the field for their career. Why would you invest so much in getting a degree that sets you up for a job that you may only do for a couple of years and doesn’t pay enough to enable you to be able to afford to have kids? This has driven down how long people tend to spend in role and limits what they can build that lasts before they move on, often to a vicar training establishment.’[8]

No role models

The decline in the number of students qualifying and serving in Christian youth work and ministry settings has meant that there has been a decline in the number of role models in churches and Christian agencies, and thereby a decline in role models for the next generation of students. They have not seen the impact that a trained and competent youth/children’s worker can deliver and thus they not seen the value and importance in this type of work. In the early 2000s, I was Director of the Centre for Youth Ministry (now the Institute for Children, Youth and Mission), and our own internal research on what attracted new applicants to the programme indicated that the most effective people to recruit new students were the current students. By implication, the less role models there are, the less young people approaching adulthood capture the value of a Christian youth work/ministry vocation.[9]

Pandemic

The academic years 2019-22 have seen the biggest challenge to traditional learning of almost any period in educational history. The global pandemic swept through and brought with it significant changes to the way learning was delivered and the way that all life, not just university life, had to be lived! This season has come off of the back of the austerity measures in England which have decimated open youth work by local authorities.

Before the arrival of Covid-19 the major political parties and the government, had all been talking about increasing spending on youth work across England. This talk has now evaporated as a result of the financial issues raised by the necessary response of the government to the continuing crisis.

Sarah Fegredo’s reply to Paul Friend’s article mentioned above, argues that the totally different experience of the Covid-generation calls for a greater commitment to training

Our post-COVID world is much more complex and challenging than anything we have experienced before and if churches are to face up to the task, we need those who work with young people and children to be well-trained… to work with young people whose lives have been shaped in ways that no adult can fully understand…

I would argue that no adult can share the experience of this COVID generation: those who have come to adulthood in a global pandemic, with schooling disrupted, mental health challenged in ways we cannot imagine and support structures disappearing overnight! How much more so now do young people and children need workers that really know what they are doing.[10]

The result of the impact of the global pandemic has been a huge decline in the numbers of children and young people in our churches and ministry events, which in its turn will have an impact on recruitment to training programmes. Many churches have also experienced a decline in volunteers available to minister to children and young people. Volunteers are at the heart of good youth and children’s work and in order to develop such work and those who volunteer, it is important to employ a worker to take the time to develop the work and to support and sustain the volunteers. Now more than ever, there is a need to invest in a qualified and trained workforce.

Low training numbers

With the decline in numbers of children and young people over the decade, and the decline in finances available, many churches have expanded the role of their worker to cover children, young people and young families. This has, for some, been the way in which they can continue to employ a staff/ministry team member and retain staff. Colleges and training agencies have restructured their programmes to be able to meet these new needs. However it does not make for an attractive job description, to be expected to do everything for the 0 to 18s and their parents!

Low numbers have also meant that colleges and training agencies have had to re-think ways in which they deliver these courses. Some have concentrated learning in teaching weeks, and some have begun to move teaching online to reduce the costs of delivery of learning. In preparation for the Sep23 cohort CYM have moved to providing fully online learning, whilst Moorlands are moving to mixed-mode delivery. The jury is still out concerning whether you can teach people how to have in-person relationships with individuals and groups using non-contact/online learning systems, and the Education & Training Standards Committee, who set the standards for youth work training, are monitoring these developments very carefully.

The future

Now, more than ever, churches and Christian agencies need to invest in training people for the long haul of meaningful, relational youth work and/or work with children and families. We are at a crisis point with the low numbers of young people in our churches. Open youth work[11], which has been part of the commitment of many churches to their local young people over the years, has declined as a result the issues raised above. If we are to see a new generation of young people wanting to grow in Christ and impact their world, then the churches and Christian agencies need to raise their commitment to and payment for training, and to improve the terms and conditions for salaried workers.

Summary stats in a nutshell

1. Churches with youth, children’s and families workers tend to be the ones that are growing

2. Those who have a qualification stick in the work longer

3. Low pay is a key factor dissuading people from wanting to train

4. With fewer wanting to train, Colleges have had to adapt their courses

4. Fewer role models mean fewer have ambitions to be work with young people

5.. The jury is out on new online training methods

Further information

For details of all the higher education programmes and qualifications available in the Christian youth and/or children’s ministry sector, do head to the CHRISTIAN YOUTH WORK TRAINING website at cywt.org.uk This site is run by David Howell with support from Churches Together in England (CTE).

For more information about the UK Christian Youth Work Consortium please head to their page on the CTE website at cte.org.uk where you can find out more of the work and, if you wish, sign up to the regular network email.

You can contact David through his email address davidhowell@cywt.org.uk

Results

2.1 Total Numbers[12]

Figure 1 – total numbers of undergraduate and postgraduate students on Christian youth and/or children’s work/ministry programmes across the UK

2.2 Professional qualifying Christian faith-based programmes

Figure 2 – total number of Christian youth and/or children’s work/ministry students on professional qualifying and non-professional qualifying programmes

2.3 Recruitment

Figure 3 – Total numbers of students recruited onto higher education programmes for both the professionally qualifying (JNC)[13] and non-professionally qualifying programmes

[1] Brierley, Danny, (2003), Joined Up – An introduction to Youthwork and Ministry. Cumbria: Authentic Lifestyle p52

[2] Howell, D, (2022) Longitudinal research into student numbers on higher education programmes in Christian youth work https://cte.org.uk/app/uploads/2022/08/Student-Numbers-Report-to-Training-Agencies-Jul22.pdf

[3] Holmes, S., Murray, L., Price, S., Larson, M. de Abreu, V. and Whitehead, P., (2021). Does the Church have a plan for reaching children? (Multi-National Research Report) (nurturingyoungfaith.org)

[4] SWYM, 2022 Mapping the Landscape Exeter, South West Youth Ministries

[5] Ali Campbell Terms and Conditions of Salaried Workers 2019 https://www.leicester.anglican.org/news/news-stories-1915.php accessed 14Jul22

[6] Leslie J. Francis, David Howell, Phoebe Hill & Ursula McKenna (2019) Assessing the Impact of a Paid Children, Youth, or Family Worker on Anglican Congregations in England, Journal of Research on Christian Education, 28:1, 43-50, DOI:10.1080/10656219.2019.1593267

[7] Paul Friend Churches are desperate for youth workers. So why can’ they find any? 05Aug21 https://www.premierchristianity.com/opinion/churches-are-desperate-for-youth-workers-so-why-cant-they-find-any/5315.article?_ga=2.146314932.125115396.1643818237-1866513226.1643818237 accessed 08Jul22. Also evidenced in Ali Campbell’s Terms and Conditions for Salaried Youth Workers

[8] Premier Youth & Children’s Work (March 2021 Vol 1) https://www.magloft.com/app/premier-ycw?utm_source=Premier%20Christian%20Media&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=11930306_YCW%20notification%20email&utm_content=header&dm_i=16DQ,73PHE,68UIOM,SPLRJ,1#/shelf/38079/default Accessed 14Apr21

[9] The author was the National Director of CYM from 1996 to 2009 and evidenced applicants citing youth workers/ministers as being the most important person in their decision to apply.

[10] Sarah Fegredo Why can’t churches find youth workers? A response to Paul Friend 13Aug21 https://cym.ac.uk/why-cant-churches-find-youth-workers-a-response-to-paul-friend/ accessed 14Jul22

[11] Open Youth Work is the phrase used for work with any young person who cares to drop-in, whether or not they are part of the local church or Christian agency. This has been the traditional youth work undertaken by local authorities in England until the financial crash forced the majority of LAs to pull-back to targeting youth work on those who had identifiable needs.

[12] All numbers are “full-time equivalent” (FTE); for example a part-time student is normally 0.5FTE

[13] The professional qualifying recognition in youth work is sometimes referred to by the acronym JNC (Joint Negotiating Committee for Youth and Community Work) which agrees standards and programmes from Level 2 to Level 7 in England, with similar bodies in the other nations.