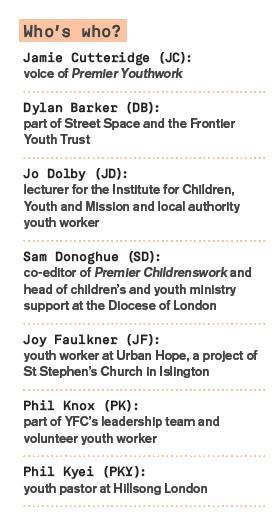

JC:What was the first thing that jumped out at you from all this?

PK: The question about face-to-face youth work hours is probably the most concerning question in there, especially as people are more likely to bump up the number of hours they do. The stat that 75% of [full-time employed] youth workers spend eight hours or less face-to-face is extraordinary.

JD: It made me want to ask if there’s a difference between church-based and other types of youth work…Maybe there’s the youth group on a Sunday because that’s where a lot of church youth workers focus their time. I wonder whether if you surveyed people who were schools workers or who are more missionally focused rather than in a particular church, you’d find that the hours increased? I was also wondering in terms of their job title, would it just be ‘youth worker’? Would the increase of the use of ‘children and families’ worker’ increase it?

So many job adverts now are asking for youth/children/community/everyone workers...

SD: The broader job title means that they are probably doing less. They’re doing a little of everything, which means they are less able to sink their teeth into one area and really get involved in it.

DB: I was also wondering about youth workers’ access to young people. If you’re a church that can afford a youth worker, then do those young people have music lessons on a Monday, swimming practice on a Tuesday and so on? Add the rise of social isolation for young people when they’re sitting at home gaming. I wonder if those things factor into it.

JD: And there’s all the management and admin involved in an oversight role and making the youth work happen but not actually doing a lot of it themselves.

SD: Without wanting to be unkind to youth and children’s workers, it’s probably not their strongest skill set. That back office management is normally taking them a lot longer than it would if you gave it to an admin person and released the person to go and do their ministry and their gifting, which is hanging out with youth people.

JF: There’s a lot of paperwork attached to youth work, and that’s not anyone’s fault. It’s legislation and all sorts of stuff. If youth work is safer and it’s targeted and more effective… if those eight hours are eight good hours, then what’s the problem? It’s always got to be quality over quantity of time we’re spending with young people.

JD: I think a lot of it depends on how you see your role as a youth worker. If you have more of an ethos of your job being about facilitating others to engage with young people – through recruiting volunteers and training others – perhaps you do less face-to-face but actually you facilitate more face-to-face to happen because you see your role as facilitating rather than face-to-face youth work.

SD: I agree. In most job descriptions we see the first section is usually about maintaining what the church has got. The youth worker is often a reaction to a perceived sense of losing children as they leave the Sunday school. Churches think, ‘We’ve got to do something’, and the response is a youth worker. The rest of the job description is to go and do mission with whatever time you’ve got left!

JF: Maybe we should be talking about creating hospitable environments for youth workers to do stuff in. It’s too much of an ask of people who care about young people to sort of say, ‘We’ll give you money to start a project, but you’ve got to fight everyone and you’re going to have to do it alone because we haven’t got enough money.’

PK: One of the detrimental aspects of professionalising youth work is that the church devolves responsibility to that sole youth worker and it’s become less of a team game. Great youth workers of any full-time nature will gather a team of volunteers around them.

JC: What else stood out for you?

PKY: It was the stats about parents that stood out for me. Within our church we’ve been looking at that same statistic because we’ve got a lot of single-parent families where the mother attends church and we soon find by the time they hit the 11-14s youth ministry that number starts to fall away. But if the father attends church, whether that’s as a part of a two-parent or single-parent family, that statistic is far higher in terms of the child attending church. We’re looking into this in terms of engaging with parents and actually finding out what the barriers are in terms of them attending church. We also have a lot of kids in youth ministry and their parents don’t come to church, so they are very much first-generation Christians in their households. That brings challenges and we want to make sure that there aren’t barriers where parents might be preventing their children from coming to church. That may be something that quite a lot of churches are doing already, but for us reaching out to parents is something new.

SD: Home visits are a really effective way of engaging and going on to someone else’s territory and being very un-British. In London, in our immigrant communities, crossing the threshold and receiving their hospitality is nothing like our culture, but it’s very much part of pretty much every other culture in the world. It’s a very powerful thing to do.

JD: It’s good to remember and look at who had been asked: 89% identified themselves as Christians and 66% of those were female; 41% were over 18 and 83% were white, so there’s a lack of diversity. It would be interesting to break it down and see how it’s different for black minorities or LGBT young people, and what their perceptions are and understandings are of things like the Bible and prayer. I think it would actually be really exciting to do a big survey of young people who had nothing to do with church about how often they pray.

DB: I wonder in terms of young people’s views on sex, and how often they attend church, what messages are coming out of church and what messages are coming through parents’ behaviour. The scary thing [is] that 21-22% of young people think that gay marriage should be made illegal.

JD: But then only 33% said they saw homosexuality as a sin…

SD: And two-thirds of that 33% want it to be made illegal. It’s interesting, isn’t it? We’ve got to find a better way of measuring children’s religious affiliations than believing our doctrines.

JC: Young people who go to church but don’t go to youth group have a ‘traditional’ view on these things, but generally people who go to youth group – even those who identify themselves as Christians – would have more ‘progressive’ views. So perhaps youth groups are doing a better job of showing them that there are different ways and different beliefs, and that you can be a Christian and not necessarily believe ‘x, y and z’.

PK: I always think you’re far more likely to talk about sex in youth ministry. I don’t think I’ve ever heard a sermon at my church on sex, whereas I’ve heard quite a few sex talks – some good, some bad – in a youth group setting.

JD: I think that only 33% of people considering homosexuality a sin was quite a big shift. I think if you’d done that even five years ago you would have come up with a very different statistic. I think it’s interesting that we’re starting to see a reaction to some of the cultural shifts we’ve seen outside the Church as well. And that’s starting to have an impact on people’s views, even when most of those people identify themselves as Christians.

JF: Most of the young people I work with aren’t Christians and wouldn’t identify themselves as Christians. I think with them you’d get more than 30%; more conservative. They’re more terrified of sexuality and of thinking about it at all, and I think they’d be much more likely to say that it’s a sin. Outside the Church, people don’t really talk about it at all in terms of whether it’s right or wrong. Young people are kind of left on their own to figure that out by themselves. There actually can be more hostility because of that, and I’m always surprised by that, whereas in an environment where there’s a conversation it can end somewhere slightly different.

JC: It would be interesting to know what youth workers believe about this stuff and whether that’s reflected in their young people. And also to find out what young people think their youth workers think about this stuff. Are young people forming these opinions on their own?

JD: There’s the assumption that there needs to be a doctrine, whereas actually I think that a lot of youth workers recognise the dysfunction of an inherited theology. It’s not our job to tell young people what to think, but we walk alongside young people and journey with them as they wrestle with God to work out the answers for themselves. This might be a generalisation, but I think of the youth workers I know and they’re much more likely to say, ‘I don’t know.’

PK: I think that youth workers do feel like they have to have a stance.

PK: Probably.

DB: Do they feel like they have to have a stance because they represent the Church?

PK: No, I think because they feel they have a responsibility to the young people they work with and they want to provide some certainty for them.

PKY: Yes, they have their stance on that particular subject, but it’s more important to walk that journey through with that young person and help them to wrestle with God and find their own revelation.

JC: What about the way ‘church’ and ‘youth group’ are perceived? Church is seen as a place to connect with God. Youth group is seen as a fun place to be.

JF: I think Sunday mornings are alien to everybody. I think church is a weird thing when you properly think about it. Everyone comes in, sits in rows and sings. It’s weird! I know that memory of church for young people is disintegrating…but when young people die or something really bad happens, young people want us to open the church. These are young people who have never sat in rows, never watched a thing from the front, never had the music, but they still want that. They still want a space where there is structure and order and some sort of religious meaning.

PK: I think generally Sunday mornings are increasingly broken in a post-modern context. I think one of the main reasons for that is that the Church broadcasts in a post-broadcast age. The primary way to engage with information is to interact with it. Most (90% cent of) churches are broadcast from the front and it’s hard to engage with that. I think youth ministry has been ahead of the curve for years on this. Most of our youth ministry is participatory. But my reflection on the kind of ‘fun place to be thing’, is that I think we just need to hold that tension in with thinking about whether we’ve dared them enough. I’m absolutely compelled by the Shane Claiborne quote that says if we lose a generation it’s not because we haven’t entertained them enough; it’s because we haven’t dared them enough.

SD: If that was your youth group, would you say that if 45% came there primarily to have fun you’ve failed? We have the battle in children’s work that most children come to learn about God. So if you did this question with children, the children would say they come to learn about God. Well, as a children’s worker I’d say that’s not great and we’d rather they came to encounter God than to learn about him.

JC: What about the stats surrounding evangelism? It’s not seen as a priority. What do we make of that?

PK: That was the one they had to rank in order, and that was after Soul Survivor…So if you rank Soul Survivor in order (one to five), it will go: experiencing God, community, teaching, social action, evangelism. If you were asked that question on a mission trip to Bangladesh you’d probably say that social action was the most important and so on.

SD: There’s an issue with how we define evangelism, isn’t there? If you want a group of people who are better evangelists than teenagers, I present to you the under-11s! That’s because they don’t know the fourpoint gospel, so they don’t know how rubbish that evangelism is and how awkward it will become! All they know is about sharing how much they enjoy church and how much they enjoy Christian life and how much this culture is a good thing for them. So they’re the most natural evangelists because they’ve never been taught how to do it.

PK: I think this would be indicative of the whole Church. I don’t think it’s particularly young people-centric. I think if you asked a load of adults what they think about evangelism you’d probably come up with something similar. Therein lies one of the challenges. We’re not modelling mission across the whole Church, necessarily, and young people pick up on that.

PKY: Seeing young people engaging and inviting their friends – and, as you were saying, just living the life – the fruit of that is their friends experiencing Jesus through how they live. I think it’s positive to see young people, from what I come across, engaging in that and actually inviting their friends to youth group or church. We are seeing numbers increase, but that’s something which has been spoken about from the platform of the wider Church and they are engaging in that.

JC: That’s great to hear. But I wonder in the rest of the Church where we’re not seeing that, if we’re not seeing that as a consequence of the way young people view their own faith. If going to church and having a faith is part of your identity rather than the core aspect of your identity, then it becomes less important to tell your friends about.

JD: I don’t want to change the subject too much, but it made me think about how we’ve lost that ability to release young people as storytellers; that it isn’t about bringing them into something necessarily, but it’s about telling their friends what’s going on in their lives. I think one of the stats was that about 20% never read their Bible and quite a lot of others said they didn’t read it regularly. It made me feel a bit sad, but also excited in terms of what a massive opportunity we have to do loads to reimagine and re-explore what it means to engage with the Bible and to use that.

DB: It’s interesting now with social media and young people sharing probably more than ever but not being empowered to share those stories.

JD: I work with some young people in a local authority club but they also go to a church youth group and I know the church youth worker. Sometimes I hear them talking about what they’ve done in church youth group. They watched the God’s Not Dead film and I think at the end they got challenged to post a message to all their friends saying ‘God’s not dead!’ This young person just did that and got a load of responses saying ‘What?’ She didn’t know what to do after that. She just did what she was told and when people responded she didn’t have a reply. Maybe more of what we need to do around evangelism is to train people up to be storytellers.

PKY: I recently went to a youth marketing conference and lots of organisations like MTV, Facebook and Twitter were there. MTV did a session and said that one of the biggest shifts they are making to engage with young people is actually telling stories. You can go on their Instagram feed and social media feeds and they are telling stories about things that have affected young people…They’re finding that they’re gaining more and more attention from young people because you’re telling a story about an experience that a young person can relate to or grab hold of.

PK: I also think that with storytelling we need to recapture some of the conflict that’s in the gospel. Jesus can absolutely transform a life in a moment. I think we’ve lost some of that and one of the reasons young people feel less confident in evangelism, and maybe why we feel less confident in evangelism, is because we don’t talk about or don’t see enough of Jesus transforming a life in a moment.

JC: As a children’s worker, what are the things that you take away from this data, Sam?

SD: I’ve been of the opinion for a long time that in children’s work we don’t set children up to be teenagers at all really…We haven’t given them the ability to develop their own theological thinking, their own reflective practice, their own ability to connect with God outside of meetings. It frightens me that I hear experts in youth work saying that we need young people who can tell stories. That, for me, says that children’s work has failed if at the end of it they can’t tell stories and at the end of it we haven’t given them the theological tools to think about stories for themselves. We just give kids doctrine and try and reinforce it, and then actually the process of becoming a Christian starts in the youth group…We’re going to keep sending you young people and the first thing you’re going to have to do is deconstruct everything we’ve done for 11 years before they leave, and you’ve got about six months. And if you fail in those six months, it’s your fault!

There’s a connection that we haven’t really made, which is a real shame because children don’t wake up one morning and are teenagers and need to be in youth group. There’s a transition over time and we haven’t achieved this at all.

JD: I think the idea of transition is really key, and that’s something that both disciplines need to do more on. There are a few conversations around at the moment about the mix of children and youth work. A lot of people think it’s a bad thing and some think it’s good to have a more joined-up approach, and it makes people think about the whole family. You can’t really be a youth worker unless you consider the context of that young person. How can we work more with children’s workers? Should we be doing more joined-up work? Should we be trained in both disciplines so that we at least understand the development of a child?

PKY: I think the key word is transition. It isn’t, ‘Hey, you’ve reached year seven. You’re someone else’s problem now.’ But when you can say, ‘Here’s everything about this person’ or, ‘This is what this person’s going through.’ So you’re getting this 11-year-old and you have a background and a picture of what they’re going through and where they are with their journey.

SD: Working with year fives is really great. One of the things we quite simply, but fundamentally, get wrong is that we take our cue from education when we transition kids. We often transition our church groups at the same time. Rather than creating some stability and continuity when everything else has just gone bonkers, we join in and do it too!

JF: We’re trying to stop transitioning at all now in terms of our sessions with young people. When everyone goes into year seven we’re just going to leave them alone and keep running the club, so that as they get older their clubs don’t actually change and their volunteers don’t change. They change and so much is changing and we’ll just stay the same around them. The new younger ones will just have to join a new group.

DB: Street Space’s approach is that you work with a group and then generally there’s a core group and a fringe group around that. You work with that group from whenever you meet them and you stay with them.

JD: That emphasises the need for a more joined-up approach. If all you’ve ever been trained to do is work with young people from 11 upwards you’ll hit trouble.

SD: I think we’ve created a false specialism in children’s work. I don’t think it’s as different as people think. If you’re in an educational model you have really clear specialisms because you’re teaching and you have to teach age appropriately. But if you’re in a model which is about building community and space for children to be known, I think you’re not looking at something that is massively specialised.

JC: What about the other end of the age spectrum?

DB: Well in terms of transition, how does a young person leave youth church and enter mainstream church? How different are those experiences? If you look at it over the last 30 years, whatever happens in youth group gets picked up by the mainstream church.

JD: We need to really move away from transition being when people are 18 and going to university. But actually a lot fewer people are going to university and that’s only going to increase with more training-based qualifications. There’s an assumption that they’ll turn 18 and move away, but that’s happening less and we’re not really geared up for that, so the youth group stops when they’re 18.

PK: But that’s got to be unusual, right, in terms of even identifying emerging adulthood as a unique phase of life? I think in most churches the posture would be that at 18 they’re ready to come into mainstream church.

JC: Let’s finish by talking about crisis. There is this narrative of crisis and I think you can use these stats to say whatever you want about that. You can say, ‘Hey, 90% of young people seem to be Christians, that’s amazing!’ or you can say, ‘Youth workers are only reaching people whose parents go to church.’ Do you think youth ministry is in crisis or is it going through a time of transition? Phil, you’re the biggest optimist I know, tell me why youth ministry isn’t in crisis…

PK: I think youth work has always been hard. You read quotes from Pliny and Virgil and they’re saying things like young people are running riot and they’re badly behaved. Jesus found youth ministry hard. I think young people still represent our greatest chance for revival in Britain. All the research and all the stats about when people give their lives to Jesus show that our greatest opportunity is reaching young people, so youth workers need to be as invested as possible, not only in the young people in their church but also out there in their community and in a whole range of innovative ways…I think the more we invest in it, the more fruit we’ll see.

PKY: I’ve only been in youth work for four and a half years, so this picture of youth work is what it’s always been for me. In terms of crisis I just see it as the norm…We’re probably forever going to be chasing the ball, so to speak, but I think that there are amazing things going on, and more and more young people are coming to know Christ. The work of the Church and youth work becoming more professional and putting structures in place will mean that it will continue to advance, but there will constantly be that tension and constantly be that demoralised and disheartened feeling at times because it’s the nature of the business we’re in.

JD: A better question than, ‘Are we in crisis?’ would be, ‘What is there that’s in crisis that reveals opportunities to us?’

DB: The economic downturn hasn’t just hit youth ministry. So there’s a massive opportunity where youth centres are closing down to engage in your community. And if, as the stats here indicate, we’re working with a narrow band of young people, do we want to stay on that trajectory or do we want to break out of it? I’d suggest the latter.

SD: When I was first in the role, I was sat in a meeting with the Bishop of London and a load of new clergy. One of the new clergy said: ‘How is the Church responding to the crisis in the Church?’ And the Bishop of London said: ‘There is no crisis because there was no golden age…’

We’re not in a crisis, we’re just having to adjust to the world as it changes around us. And we always will. If we’re not, then it’s more of a problem, because it probably means we’ve stopped thinking and we think we’ve made it... and then we really will have a crisis.