- Home

- About

- Topics

- Parenting

- Stories

- Growing faith

Christian devotions at home for children with additional needs are hard but worth working at

Christian devotions at home for children with additional needs are hard but worth working at Parents are the key to bridging the gap between church and school

Parents are the key to bridging the gap between church and school A tool to help your child ‘take captive every thought’ and walk in freedom with Christ

A tool to help your child ‘take captive every thought’ and walk in freedom with Christ ‘What do you do?’ A Christian mum finds the question triggered more than she expected

‘What do you do?’ A Christian mum finds the question triggered more than she expected

- NexGenPro

- Donate

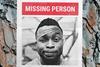

Missing Person: The male children's leader

By Alex Taylor is the Resources Editor at YCW Magazine 2019-10-22T00:00:00

If you take a look around the children’s work at any church on a Sunday morning, chances are you won’t spot many men. But why aren’t there more male volunteers in children’s work? Alex Taylor takes a look at some of the underlying issues

This article is for subscribers only - SIGN IN here

If you want to read more, subscribe now for instant access to 1000s of resources, advice, ideas and support for anyone involved in family, youth and children’s ministry.

PLUS receive a weekly newsletter to keep you up to date with what’s new, what’s seasonal and what’s in the news!

If you are already a NexGenPro subscriber, SIGN IN

Related articles

-

Article

ArticleHow to successfully navigate the Christmas chaos with those with additional needs

2023-12-11T11:46:00Z By Mark Arnold

It’s Christmas!! Those two words seem to divide the nation even more than Brexit has, with people falling into one of two ‘camps’… Either you started wearing your Christmas jumper in October, had your decorations up in November, and have already watched ‘Elf’ 12 times this season, or you feel ...

-

Issues

IssuesHelp, I have a child with ADHD!

2023-09-20T12:51:00Z

Sam Donoghue and Catherine Truelove give their perspective on two tricky questions asked by youthworkers

-

Article

ArticleSeptember resources

2023-09-06T13:46:00Z

With the new school term under way we have oddles of tasty resources for you on the NexGenPro website. You can simply browse to the topics you fancy and download and use curriculum for your group. Some choose to use the three year curriculum approach that NexGenPro ...

More from NexGenPro

-

Article

ArticleBeing a steward of resources for Children’s and Youth Ministry

Steve Henwood takes a look in the games cupboard and reflects on how we need to think about the ‘stuff’ of youth ministry and how we can get more

-

Article

ArticleGet yourselves a silent disco headsets – the multi-faceted ministry tool

2024-01-11T11:28:00Z

Steve Henwood is convinced that your youth ministry could have a new dimension if you can raise the funds for this versatile gadget

-

Article

ArticleMore tools to help the Bible ‘stick’ in your life and those you serve

2024-01-11T09:42:00Z By Tim Alford

Tim Alford continues his exhortatation for us to make the Bible a vital part of your life

- Topics A-Z

- Writers A-Z

- © 2025 NexGen

Site powered by Webvision Cloud