Tim Gough puts our youth work in a historical context and asks: “What’s next?”

It’s the mid-90s. Pogs are in, tamagotchis swing from every key chain, Britney Spears is about to make her autotuned debut, and Christian youth ministry is the place to be. There are more Christian youth workers in post than Britain has ever seen before. DC Talk and Delirious? are selling out stadiums, youth festivals are popping up like whack-a-mole and every church worth its salt is hiring its very own youth worker.

Boy! Those were the days, eh?

Where are we?

When I turned 21, I landed my first youth worker job. I had my own office, my own computer, my own mug, my own whiteboard markers and two of my very own youth groups. It was awesome! This was 15 years ago though, and it came after being turned down for dozens of other jobs. After having been rejected so many times I felt hopeless and desperate. Even though I had a degree I was too young and inexperienced to be trusted with an entire ministry. Finding a job was harder than passing my driving test – and that took four attempts!

Now I sit on the other side of the desk. I thought getting a youth work job was hard then, however that feels like nothing compared to finding youth workers to fill positions today.

It’s possible to work out from UK denomination attendance reports that at least 75 percent of churches have no youth provision at all and, conservatively, 70 percent of the youth work which does exist is run by volunteers. Much of the rest is run by part-time or job-share youth workers, including curates and assistant ministers. There’s not actually a whole lot of full-time Christian youth workers around today, and even fewer are being trained up.

The latest report from The Christian Youth Work Consortium suggests that the number of youth and children students in validated training has declined almost 52 percent, down to 299 (and only 75 on qualifying JNC courses) in just over a decade. If you were to just look at specialist youth-work courses this number drops again, and it is likely that less than half of these students would complete a full degree.

There are only eleven UK Bible Colleges left offering youth-work degrees. Several have consolidated their youth modules into other programmes, dropping the specialism, and other training centres have closed entirely. You can also count on one hand the number of youth ministry books for these students published by UK authors in last decade.

Does it feel like Christian youth work is disappearing? I mean, there are fewer churches looking to employ youth workers today, and even for those who are, there are far fewer candidates applying.

So, are we done? Should we all retrain as door-to-door salespeople (we’d be good at that!), or ‘graduate’ into ‘proper’ ministry? I’ve been a youth worker my entire adult life. Outside of this I have no actual human skills, so I really hope not or I’m scuppered!

As a clinically diagnosed optimist, I believe there is hope. The branch might be creaking, but God’s plan for youth ministry is far from over. In fact, I suspect he’s just getting started.

Where have we been?

Modern youth ministry is a toddler compared to other ministries. It’s only really been around since the 1950s. As a movement, we’re only just learning to walk and there’s still drool on our chins.

In many ways, today’s UK youth and children’s work was born out of the Sunday school movement in the 18th century. When state education eventually took over much of what Sunday school taught, churches were left with suddenly declining small groups of young people who had always met separately to the adults during worship. However, rather than try to join back together, we continued to meet away from each other and the separation grew.

Looking to stem the decline and reach those outside, the first parachurch youth mission groups were born. Scripture Union, the Boy’s Brigade, and soon after the Girl’s Brigade, started to connect with young people on the edges of church culture. They all did great work, but the churches themselves had no mechanism in place to fully embrace young people back into the body.

It wasn’t really until the end of World War Two, and the emergence of adolescence as a particular branch of social-psychology, that the specific youth ministry we know today took shape. Young Life and Youth for Christ started to run attractional youth work, using more youth-specific language and approaches with the focus on an upfront persona. Soon after, John Wimber visited St Andrew’s Chorleywood, which birthed New Wine, which in turn developed the successful youth festival Soul Survivor.

Early youth workers were forged in the world of these events and festivals, and they operated, by-and-large, separate from the wider church body. What had started with the Sunday school model had become institutionalised.

The result has been youth work that largely sits outside of the rest of the church and is run by short-term, upfront, high-energy individuals. This hasn’t been sustainable as an approach and has left a wake of burned-out youth workers in a Church that’s drifted further from its young people.

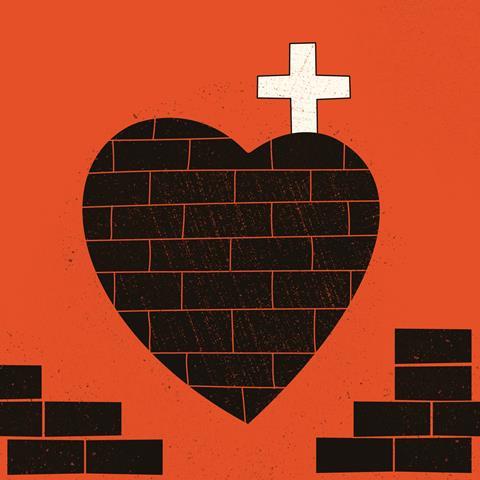

In the 1980s, one quick-witted youth worker described this relationship between the Church and youth ministry as “the one-eared Mickey Mouse” (Stuart Cummings-Bond, ‘The One-Eared Mickey Mouse’, Youth Worker Journal 6). ‘Church’ was the face, and ‘youth work’ the ear. The idea was that the church and the youth group had become two separate entities; connected…ish, even linked…kinda – but not truly one thing.

My late Uncle Bob was awesome. I always thought he was a real-life pirate – he even had a hook for a hand! He served in the British Navy and his arm was damaged in an explosion during the Falklands War and he had to have it amputated. When I was a child, I asked him innocently: “Hey, so what did you do with your severed arm – did you keep it in a big glass jar?” To which he simply replied: “Binned it. Didn’t work anymore.”

My Uncle Bob knew it, and so do we. Our bodies do much better when they’re in one piece!

If I was to saw off your legs and place them in a box twelve feet away from the rest of you, are you or your legs going to be particularly happy about it? What about in ten years’ time – will it get better? What if you were to duct tape them back on?

This goes for any and every limb that we cut off the body and put into its own homogenous ecosystem. Glass jars just don’t work. The question this raises is just how many limbs can be removed from the body, and for how long, before the body itself becomes just another one of these dying limbs? The more we chop the Church up into smaller and more specific groups, the more the whole body suffers. I think that’s what we’re seeing today.

Where could we be?

I think trying to resuscitate the youth ministry of the 90s is a flawed idea. We can retain all the good that we learned during that time (relationship focus, cultural sensitivity, relevant communication, missional heart etc), and still find a way to bring youth work back into true coherence with the rest of the Church.

This doesn’t need to mean losing our youth groups, training, conferences or youth workers, but it would mean starting from a different place, shifting some of our strategic focuses and developing slightly different skills.

It would mean starting with the assumption that the goal of youth work is to create worshippers within a larger worshipping body, to help young people become whole and healthy members of a wider community of faith. And that would mean a youth worker’s job becomes primarily about facilitating, supporting and empowering a much wider group to connect with young people.

The youth worker’s role changes then to facilitate truth, compassion, discipleship, worship and mission between young people, the church and the broader community. The youth worker becomes the junction box not the electricity. This requires skills like mediation, management, direction, discernment and oversight – at least as much as the ability to communicate with teenagers. This facilitator needs a keener awareness of theology and a passion for more than just young people. They need to be church builders, not just rebels.

Church is fundamental to healthy youth ministry. You can’t truly have youth ministry without it, and church is far worse off without young people. Does this mean church needs to change? Sure! But so do we.

There’s work to be done on both sides of the one-eared Mickey Mouse but the perception that we are all emphatically one body is a good start. So, youth workers, let’s start with church, supplement that with specialised ministry, help young people take responsibility for their own faith, champion parents, and then get out of the way!