Culture is this weird, two-way stream. Sometimes culture informs us, and at other times the popularity of one particular piece of culture tells us something about wider society. Take One Direction for example; ‘You don’t know your beautiful’ is the best pop song of the last ten year’s (this isn’t up for debate), and yet it doesn’t really say anything particularly interesting. However, the popularity of that song and that band does say something interesting. These five moderately attractive, somewhat talented young boys are freakishly, terrifyingly popular among (female?) teenagers. The individual level of fandom is a product of the collective, i.e. no one fan would be as obsessed with the band if it wasn’t for the wider obsession; with each new fan added, the collective level of obsession rises, with teens desperate to be part of something bigger than themselves*. The whole thing works like some kind of perpetual-motion machine - like Harry Styles on a hamster’s wheel, dragged forward by his own momentum. (*An important note - when I talk about young people wanting to be part of something ‘bigger’ than themselves, I don’t necessarily mean bigger in terms of numbers, more an idea of a story larger than the individual.) Perhaps the phenomenon of One Direction (and their 1Ders) is the latest expression of something we’ve seen among young people for as long as there have been young people: they are desperate for community and to be part of something bigger than themselves. For a while the Church played that role, but the emergence and subsequent change in youth culture over the last 100 years shows a definite shift. Pop culture has taken the place of the Church among young people. Seriously. The ethos of society is spelled out in Miley Cyrus’ songs, morality is played out in front of our eyes on Big Brother and then discussed and broken down on its myriad of sister shows. But it’s bigger than that, because Church has never just been about brainwashing young people (hopefully it was never about that). Church, in its very existence, created community; it made people feel part of something bigger, it invited them into the story that plays out across creation. It still does that. We still do that. But young people are congregating and creating community around films, TV shows, songs and books. Their community is now largely outside of the Church doors, and outside of the youth club. So what is being communicated to young people through this cultural community, and which books, TV shows, films and music are they flocking around?

THE BOOK

Now turn to page 234 of the pew bibles. This week’s reading comes from the biggest book of the last few years, set to be possibly the most important movie of 2014. The Fault in our Stars, which tells the story of a doomed romance, was a smash hit even before its release. Here’s the thing about this book: it gives teenagers credit. It deals with adult themes, in a teenage context; love is seen as a real emotion, not as a wishy-washy feeling for a weekend, and death and pain are real things to be dealt with. It’s real and that’s why it’s scaring adults and The Daily Mail. Ultimately the tragic realism of The Fault in our Stars affirms young people’s ability to make and live with difficult, gut-wrenching decisions, while also showing that there is hope in places which seem hopeless. While young people are forced to face ever more difficult situations as they grow up, it is no surprise that a book about hope showing up where you least expect it is proving so popular. Unsurprisingly, certain tabloid newspapers kicked up a fuss about a book which portrayed such a real depiction of teenage life. Green’s response was wonderful: ‘The thing that bothered me about the Daily Mail piece was that it was a bit condescending to teenagers. I’m tired of adults telling teenagers that they aren’t smart, that they can’t read critically, that they aren’t thoughtful, and I feel like that article made those arguments.’ The popularity of The Fault in our Stars demonstrates that young people are capable of more than we think, capable of dealing with big, scary, complex issues – and they want us to know that. There’s an aspirational aspect to the book as well, inspiring young people to be better, to think deeper, to live lives beyond the immediate, shallow existence and culture that the media would have them consume. As Martin Saunders said in a piece for our sister title Christianity: ‘Augustus and Hazel (the central characters) discover important and countercultural truths about themselves: that they are unique; that they are loved; that life is worth fighting for. What great messages these are for young people – any people – to read and absorb.’ What’s also interesting is that, like many of these cultural phenomena, Green has built a strong, thriving online community around his writing. Green’s ‘Nerdfighters’ as they are called, have such a fierce and committed online presence that they have raised hundreds of thousands of pounds for charity, helping various causes worldwide. Reading John Green is not a passive experience - it’s a worldwide movement to be part of. Green’s books sit alongside the Harry Potter and Twilight series as the most popular among young people in recent years. While the books are set in wildly different environments, they do share some common DNA. In all of these books teenagers are put in ‘adult situations’ and forced to deal with things beyond their control, be it death, evil wizards or vampires. As spurious as that may sound, there’s something in this, something we also see reflected in The Hunger Games films. This desire among young people to be seen as capable, as important, as holding a vital place in society seems to be key – and these books (along with the equally popular Hunger Games trilogy) do that.

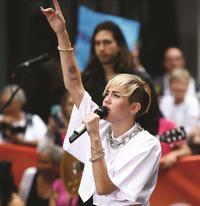

THE WORSHIP

All good churches need music. If ever one moment summed up a pop-cultural era it would be Miley Cyrus’ performance at the MTV Video Music Awards. The meeting of Cyrus and Robin Thicke, complete with foam finger and ‘twerking’, epitomised 2013. (If you haven’t seen it go and look at it on YouTube. Actually, on second thoughts, if you haven’t seen it – congratulations, you have successfully completed and won 2013, continue to 2014 you lucky so and so.) You had the younger woman, with less clothes on, and the dominant, male, sexual figure. That male figure, of course, being one best known for a song (Blurred Lines) that not only patronises women, but turns them into sexual objects and seems to exist in a grey area somewhere between lust and exploitation. It’s been an odd few years for Miley. The former queen of the Disney Channel has turned into a provocative pop star, famous for swinging around naked on wrecking balls and being suggestive with hammers. Yet she is, after Beyoncé, the biggest female pop star in the world, and as such, one of the most influential media figures of our age. Her message in her videos and appearances may be ‘Use your body girls!’ but her lyrics have a heap more nuance. In fact, ‘We can’t stop’ may be the saddest song of the year. It starts off with teenage rebellion (‘It’s our party we can do what we want…it’s our party we can love who we want’), but that final, echoing ‘We can’t stop’ sounds more like a cry for help from a generation who have partied too hard. Perhaps, in the midst of this scantily clad, sexualised individual then, we have the message that this comes with a cost – that a life of sex and booze can drag you down, that living your life in this way isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Is it that Miley Cyrus has revealed a great truth of our age but wrapped it in very little clothing? Whatever she is actually saying, it’s not the message that young people are hearing. They’re getting the sex and the fun, but the cost? That’s pretty subtle.

THE HERO

The Hunger Games has been the dominant film series among teenagers over the last couple of years. The story of Katniss Everdene’s survival in an arena defined by ‘kill or be killed’ rules, and her subsequent role in the rebellion against an oppressive government has struck a chord with teenagers both on the screen and on paper. But why? Despite the scaremongering in the tabloids, very few young people’s existence is as fraught as Katniss’s, and very few have to fight against a tyrannical regime (they leave that to their youth workers). Katniss is an outcast from the least influential district of the country, yet it is her actions which spark huge social unrest and ultimately, change. This nobody, with seemingly little influence or power, ends up starting a revolution. The film screams out that anyone has the power to change the world. Young people are desperate to believe that they matter, that they can make a difference (they do and they can, obviously) - and The Hunger Games affirms this. A film which takes an ordinary teenager and has them do extraordinary things in the midst of an awful situation was always going to grab young people, and this one has. Part of the popularity of the films is down to the star, Jennifer Lawrence. J-Law, as she is known, comes across as the most genuine person in Hollywood, a seemingly rare trait in that culture. She’s funny, self-deprecating and down to earth. Young people see through so much of the guff that Hollywood throws at them - they’re not taken in by the lies of perfection - and so when they see someone in that world subvert it by merely being themselves, it’s no surprise that they are drawn to them.

THE TRUTH

Reality TV may have risen up over a decade ago, but it remains huge among young people to this day – which tells us something very interesting. Despite very little artistic quality (in this humble writer’s eyes) reality shows such as Big Brother and I’m a celebrity get me out of here, as well as ‘dramality’ shows such as Made in Chelsea and The only way is Essex, reveal a desperation among young people to be shown something real. Though they know the reality of scripting and can see through the staging of some scenes, they also know that these are real lives, with real consequences being played out in front of them. In our culture of fake tans, airbrushing and press releases, young people are desperate for someone genuine, for someone to be honest and vulnerable, for someone to show pain and say when things are not ok, when things are not how they were meant to be. At the other end of the cultural spectrum, Sherlock is a really interesting case study. While neither real nor interactive, the community around the show, and the fandom it has created, shows this desire to be part of something real, part of something bigger than yourself (the other show which does this is, Doctor Who). The tumblrs, Twitter feeds, fan fiction and GIFs have become central to the experience of watching these shows for a certain type of viewer. The ‘interactive’ nature is something we’ve seen prove popular for years in reality shows, but more so than any others, these shows have taken on a life of their own online. There’s this weird ‘inner-sanctum’ that has been created, and an odd, symbiotic relationship between the ‘hard-core’ fans of the show and the writers (the first episode of the latest series was full of ‘hat-tips’ to hardcore fans and online communities – jokes only they would get). One member of this Sherlock community said this about the fandom: ‘The majority of fans are just enthusiastic, creative people, who love to indulge in a bit of escapism. A fandom is like a whole community and the people in the group genuinely look out for and support each other, as well as caring about the show and its cast and crew. The show is used as an icebreaker between people who then can go on and form a friendship – it’s how I met my two of my closest friends.’

THE FLOCK

Here’s the thing: the challenge posed by the church of pop culture is no different to the challenge the Church has faced for the last 2000 years. The good news is that all that young people are looking for (and are currently finding in pop culture) the Church has to offer. We have a compelling, worldchanging story, we have a community to be a part of – a place to be known and loved - and we have a God who moves among his people in amazing, transcendent ways. Our challenge is reframing our story and community to connect with this generation of teenagers. The church of pop culture shouldn’t scare us, it should excite us and remind us that young people are still searching for ‘church’ – they’ve just found it somewhere else.